January 21, 1788.

The Governor accompanied by Capt. Hunter & some other officers went in Boats to examine Port Jackson….The next day one of the Party took a fife on Shore played several tunes to the Natives who were highly delighted with it especially at seeing some of the Seamen dance.

The Complete Letters of Newton Fowell. 1786-1790. Midshipman & Lieutenant aboard the Sirius, Flagship of the First Fleet on its voyage to New South Wales.

This is the earliest account of dancing in the new land – before the fleet anchored in Sydney Cove, before the convicts had disembarked, before the colony had been proclaimed – people were dancing.

It is likely the seamen were dancing a hornpipe or a jig to the music provided by one of the marines. Music for all official occasions, as well as informal events in the First Fleet, “fell under the aegis of the Marines who, in addition to providing a force of terrestrial and maritime ‘sea-soldiers’, supplied ships with drummers and pipers”.

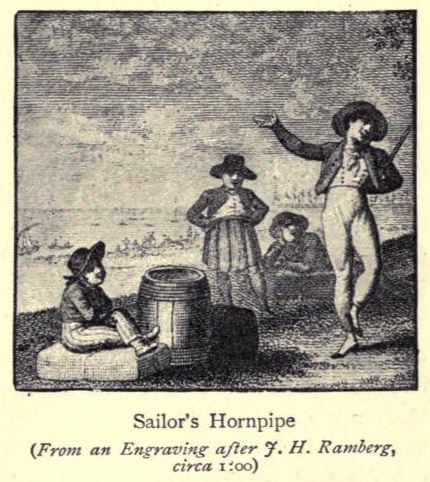

It’s thought the sailor’s hornpipe may have originated as a stage dance which then developed into an occupational folk dance. Early hornpipes were in triple time (3/2), then in the mid-eighteenth century, the rhythm changed into the distinctive common time (4/4) which is well known today. In 1740, a hornpipe was performed “in the character of a Jack Tar” at Drury Lane during the second act of The Committee, or, The Faithful Irishman. This seems to be the first association of the hornpipe with sailors.

![]()

The following year, “a hornpipe by a gentleman in the character of a sailor” was performed at Covent Garden and from that time became increasingly popular, both for actual working sailors, and for actors on the stage. As solo dance, it portrays activities in the daily working life of a sailor such as looking out to sea, hauling and coiling ropes, pumping, and climbing the rigging.

Music and dance were a part of Georgian Naval life both above and below deck. Letters dating from the 1750s show that dancing to the fiddle, fife and, drum was an almost daily occurrence on some ships, providing a source of entertainment and exercise for the seamen, and helping to maintain a connection with home.

Captain Cook, famous for promoting the hornpipe to keep his men healthy, noted on his second voyage of discovery (1772-1775) that his seamen were proficient in both country dances and hornpipes. Explorer Matthew Flinders also followed Cook’s regime of encouraging his crew to dance. Not only for common sailors, John Palmer who came to Sydney in 1788 as Purser on the Sirius, and became the Commissary of New South Wales as well as one of the wealthiest men in the colony, was a celebrated hornpipe dancer.

In 1829, G.Yates, an English dancing master, writes that few English seamen were to be found who were not acquainted with the hornpipe, some indeed “dancing it in perfection”. Schoolboys destined for a naval career, generally made a point of learning the hornpipe and during the nineteenth century it was included in the training of naval cadets. The hornpipe was regarded as “the national dance of Britian”.

The earliest know printed document in Australia’s history is a playbill advertising an evening of entertainment at the ‘Theatre, Sydney’ on 30 July 1796. One of the acts is the Humours of a Wapping Landlady, a play where the character Tom Gunter “bids the Fidler strike up a hornpipe which he fools about with such agility.”

The Humours of a Wapping Landlady, featuring a sailor’s hornpipe was performed at the ‘Theatre, Sydney’ on July, 1796. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

From the earliest mention of a seaman dancing on Australia’s shore in 1788, through to the present day, the sailor’s hornpipe has remained a part of our intangible cultural heritage. It appeared frequently on theatre programmes, was danced by convicts on Norfolk Island in 1840, and in dance schools across the colony. The tune has featured in many collections of music, from ship’s fiddler William Litten (1830) to the convict Scottish fiddler Alexander Laing (1863), and in modern times they have been recorded by collectors such as John Meredith for inclusion in Australia’s traditional music repertoire.

Sailor’s Hornpipe: Jack’s the Lad

The hornpipe tune is characterised by staccato quaver runs punctuated by the stressing of the second and third beats within the bar at regular intervals, the phrase always ending with the distinct double stress: pom! pom!

____________________________________________________________________

Music

Included is a short list of Australian sources to highlight the enduring quality of the tune in our history.

A Collection of Reels, Jigs, Hornpipes And Other Country Dances. Allans Edition No.23.

Tunes for the Sailors’ Hornpipe were included in the traditional repertoire of many folk musicians and were recorded by collectors such as John Meredith well into the 20th century.

The Sailor’s Hornpipe by George Davis, p.219.

Folk Songs of Australia. John Meredith & Hugh Anderson. Ure Smith, Sydney.1968

Sailor’s Hornpipe: Jack’s the Lad and Sailor’s Hornpipe by Stan Treacy, pp.72-73.

Sailor’s Hornpipe by Frank Collins, p.80

Folk Songs of Australia. Volume 2. John Meredith, Roger Covell & Patricia Brown.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

British Maritime Museum. Journal for maritime research. A Scots Orpheus in the South Seas. http://www.jmr.nmm.ac.uk/server/show/nav.1360

Cook, James, The Journals of Captain James Cook on His Voyages of Discovery. Vol. I. The Voyage of the Endeavour, 1768-1771

Denning, Greg. Mr Bligh’s Bad Language. Passion, Power and Theatre on the Bounty. Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Emmerson S., George. A Social History of Scottish Dance. McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal & London. 1972.

Goodwin, Peter. Men o’ War. The Illustrated of Life in Nelson’s Navy. Carlton Books, London, 2003.

Keller, Kate Van Winkle and Charles Cyril Hendrickson. George Washington. A Biography in Social Dance. Connecticut: Hendrickson Group, 1998.

Scottish Official Board of Highland Dancing. The Sailors’ Hornpipe, Scottish Version. 2004

__________________________________________________________________

The information on this website www.historicaldance.au may be copied for personal use only, and must be acknowledged as from this website. It may not be reproduced for publication without prior permission from Heather Clarke.